You have to know who you’re dealing with, who you’re making fun of. I want to make something that the person who has never heard of this character will like, as well as the person who did their thesis on them, and there’s a huge swath of people in between who may know nothing, so you really can’t phone it in. I’ll read some encyclopedia entries, essays, books excerpts, and I’ll see what their fan base is like-some historical figures have a fan base-to find out people’s reactions to this character or this event, who thinks what and why. In order to make a comic about something, you really need to know it inside and out, especially something historical, which can be complex-different sides to the story, different opinions. Sometimes you really want to make a comic about a person, and nothing comes together. And if I get lucky, someone who interests me will also come with a hook I can use to create a comic around them, whether it’s an expression, a phrase, a bit of dialogue. I was looking up Robespierre, and Danton was the figure that really struck me as the more fascinating one. That’s probably how I came across the last comic I did, with Robespierre and Danton. Sometimes you’re looking up one person and you find another person on the side, and you think that they’re even more interesting. It can also be something I’m very familiar with-like any Canadian figure-or somebody I just found out about and thought was amazing, like Rosalind Franklin. And then later on I had different opinions about it. It was one of the first chapter books that I remember our teacher reading to us in grade two. It might be something I’ve known for a long time, like with the Robinson Crusoe comic. I have an interest in almost everything, and you can see that in my comics-they’re all over the place. I gravitate toward making comics about history partly because that’s what I studied and partly because it feels very natural. I had already started the comics and had developed my style, but when I read it, I thought, This is what I would love to sound like. I also really enjoy books like Sellar and Yeatman’s 1066 and All That, a kind of muddled account of English history-though that was a later influence. We didn’t have comic shops, so the only comics I had were newspaper strips and Archie.

It’s a very tight-knit, Scottish community, so there are a lot of cheeky jokes about your neighbors-nothing very harmful because you have to live with them. Small places breed a peculiar familiarity with everybody around you. It started with the town I grew up in, which was very small. Trying to be funny and not being funny? That’s awful. You don’t want to be that person who’s unfunny. I didn’t put my name on the first comics I submitted in case people hated them. And it’s putting yourself out there quite a bit for someone who is a little bit shy, which I was. In comics, everybody is an expert in their own sense of humor, so either you’re funny to someone else or you’re not.

The Vikings were very interested in biology class, apparently.

It was a how-to guide for dealing with this breaking news. It was about Vikings! Vikings invading the school campus.

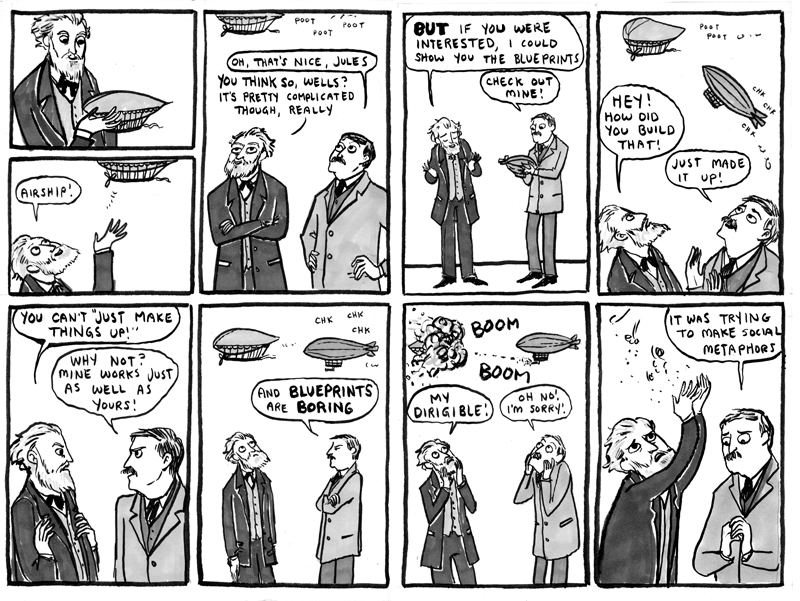

Her new book, of the same name, lampoons Kierkegaard, lumberjacks, Marie Curie, Jay Gatsby, Anne of Cleves, Oedipus, and everyone in between.ĭo you remember the first comic you drew in college? In 2007, she launched Hark! A Vagrant, which now receives more than a million hits each month. Born in Nova Scotia, Beaton studied history and anthropology, discovering through her university’s newspaper that she could put her knowledge of people, places, and dates to work in a humor column and, later, in comic strips. Little is spared her lively pen and waggish, incisive wit. Kate Beaton makes comics about the Bröntes, Canadians, fat ponies, the X-Men, Hamlet, the American founding fathers, Raskolnikov, gay Batman, Nikola Tesla, Les Misérables, Nancy Drew, Greek myths, and hipsters throughout history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)